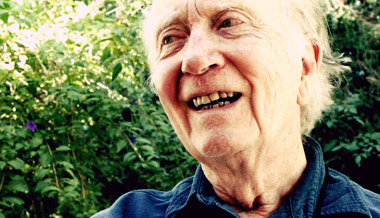

Today’s post wraps-up several reflections about John Cobb, a “process” theologian who seeks to sharpen our prophetic hearts and voices to challenge our “lesser angels” that promote attitudes and positions that are less than healthy and sometimes destructive to the planet and to relationships.

Cobb is skeptical of secularism because it leans only (or too heavily) on our contemporary, cultural reasoning and values, to the exclusion of the rich traditions of world religions (which Cobb prefers to call “Ways” instead of “religions”). However, Cobb believes the act of secularizing is essential for healthy societies and for healthy faith.

As I understand Cobb, he consults what Richard Rohr calls “the perennial tradition,” the collective wisdom of the world’s great faiths and philosophies–the common gems of insight and healthy community that are drawn from these traditions, to form a value system or worldview (my words, not Cobb’s) to enable each Way and each person to engage in ongoing self-critique.

We are in a time of heightened religious consciousness, religious competitiveness, religious schism, and religious activism. People today (more than in the past, I believe) are not hesitant to claim for their political preferences an air of divinity. Michael Flynn famously said, “America needs just one religion.” My faith community (United Methodists), which is also Cobb’s tradition, is experiencing widespread “disaffiliations” by persons and congregations. Many other faith groups have, or are, experiencing similar divisions. In this fractious period of heightened religions self-consciousness, it’s important to engage in secularizing self-criticism, which examines and (when needed) strips away the religious veneer that surrounds our political preferences, our social prejudices and our personal proclivities.

Cobb believes we need secular prophets who engage in this important work, much as biblical prophets did long ago.